Cover Image: New Chamber Ballet, Stray Bird

Photo by Arnaud Falchier; dancers: Amber Neff and Kristy Butler.

11.28.2020

Art + Space: Miro Magloire

Lauren Henkin You started your career as a composer, studying at the Conservatory of Music in Cologne, Germany. You then moved to New York to study Modern Dance at the Ailey and Martha Graham Schools, eventually turning your focus to choreography and founding the New Chamber Ballet in 2004. What made you shift from composing to choreography?

Miro Magloire People. My dream growing up was to be a composer. After a few years of studying I understood that it was going to be a life of working alone at the desk, writing and cutting and pasting (back then still without a computer: just pens, rulers, scissors and glue!) I missed being around people all day long. I missed moving. So I took the leap and went into dance: no more pens, no more rulers, but being around people and moving for hours at a time. The mental fatigue of composing was replaced by complete physical exhaustion. It was so refreshing! Ironically, now as a choreographer and company director I’m back at the desk a lot. But with two decades of physical exhaustion under my belt, I can handle it.

“I think the process of becoming a choreographer is the process of learning how to see. Because if as a choreographer you see well, then your audience will feel something.”

LH I’m very interested in psychoacoustics, or how humans perceive sound, especially as it relates to space. How do you think space affects sound and/or vice versa?

MM I haven’t looked that much into psychoacoustics. One aspect that I deal with every day is how watching dance changes how we hear music. Concert dance is often described as a merging of two art forms: the collaborative work of a choreographer and a composer (alive or long dead.) That’s a bit of an illusion. The choreography completely distorts what the audience actually hears and how they perceive the music. As a former composer I find that disturbing, and it took me a long time to come to terms with it. But that’s just how it is.

There’s a beautiful ballet by Nacho Duato, one of the great choreographers of our time: “Multiplicity,” an entire evening to music by Bach. At the beginning Duato himself comes onstage and dances a short solo asking Bach for forgiveness for (mis-)using his music. I find that very moving; it’s what I’d like to do every time I choreograph.

But if I accept that I create a new work of art, not a dialogue with the music but something that completely changes it, then I have to take responsibility and make it worth the music’s sacrifice. I can’t just illustrate the score’s structure with movement. The ballet has to have a purpose of its own. Even if it entirely depends on the music and wouldn’t function without it - it isn’t the music. It’s something new and different.

That said, we have live musicians playing at all our performances, and I know some of our fans come primarily to hear their extraordinary artistry. They also see the dance, but they’re attending primarily with their ears. And that’s totally fine.

Broken Chains, New Chamber Ballet, Grace Farms, New Canaan, CT, 2014.

In this performance, New Chamber Ballet combines music and movement as they connect with SANAA's Grace Farms construction site and each other. This video is part of "Artists Warm-Up," a series that offers a glimpse into how artists warmed up the space at Grace Farms while construction was underway in 2014.

LH In this introduction to New Chamber Ballet’s ”Artists Warm Up” project, you describe the space that a dance happens in as “like an instrument.” In The Dance Enthusiast, you also talk about how placing the audience around the stage, rather than facing it, created a more “communal experience;” that the dancers had to “relearn performing in a space where you never face away from the audience: there’s no more ‘front’, ‘back’ or ‘wings’.” Why is space so important to your work?

MM Like most choreographers I started out by designing dances based on muscle memory: arranging movement according to what it feels like to move in a certain way to a certain music or emotion. And then imagining new, different ways of feeling that, which led to new movements. And so on. The challenge with this approach is that the audience doesn’t share our bodies. The only way they connect with our work is through their eyes, which respond to things like space, line, volume, color, density, and weight. So the dancer may physically feel something, maybe weight or space, but the audience sees it rather than feeling it. A lot gets lost in this translation. I think the process of becoming a choreographer is the process of learning how to see. Because if as a choreographer you see well, then your audience will feel something.

Also, since my original training was in music, I tend to find similarities to categories I encountered there, like rhythm, harmony, etc. I always wondered what the equivalent of a musical instrument was: a tool that amplifies and replaces your voice, your physical body. That’s what attracted me to working with dancers who dance on pointe: the pointe shoe is such a tool. It allows you to do things that your body alone can’t. Another definition of a musical instrument is the interface that you interact with physically. And to us dancers that would be the floor. It’s the same kind of love-hate relationship: you need it, you depend on it, and if it’s not exactly the right consistency, surface, resilience, friction, then you’re completely lost. Minute details of slipperiness or resilience can make or break your performance. It’s the place where you and gravity meet.

We had a project a few years ago, inspired by NASA, to think about what ballet would be like in microgravity environments. I learned that none of the movements in our dance vocabulary would be possible outside of the specific gravity environment we have on earth. We didn’t pursue the project, but it informed everything I’ve done since: the importance of friction in our relation with the ground.

“…we brought some wood sticks into the hollow underground spaces of the structure and recorded their echoes there. It’s “percussion,” but actually it’s a portrait of the building’s acoustic reflection.”

LH I love the New Chamber Ballet piece, “Broken Chains,” performed at Grace Farm’s construction site, as the building was still bare and raw. There is an incredible complexity to the choreography, but also in how much impact the space, the light, and the camera work with the dancer’s movements. This is so far outside the boundaries of what I think of as “ballet;” it’s electric. What were some of the considerations that went into the choreography for this piece, especially considering all that the dancers would be encountering in this cold concrete stage?

MM The idea behind the “Artist’s Warm Up” was to challenge the notion that you first build a building and then put the art inside. Kenyon Adams, the Creative Director of the Arts Initiative at Grace Farms, wanted the arts and the building to appear simultaneously and gradually in the site’s very beautiful landscape. SANAA’s building is trying not to interrupt the landscape; could the arts do the same? Several groups of artists were invited to create at the site a year before its opening. It was striking for me how present the building already felt at this stage. It snakes through the hills like a river. The time window was quite narrow since we had to work after hours, so I started with a few existing works of mine and reset them into the building’s shell and the surrounding landscape. We couldn’t bring a live audience onto the active construction site, so it had to be a film, which completely changed the piece: what you see in the video is filmmaker Ben Stramper’s (brilliant!) interpretation of my own interpretation of SANAA’s interpretation of the Northern Connecticut landscape.

The production of this particular film was rather delicate. We have an iron rule in our company: we absolutely will not dance on concrete floors, no exceptions. It’s an unacceptable risk of severe injury for the dancer’s legs and backs. Now here it was going to be all concrete, not finished but raw, with stones, nails, splinters everywhere. Part of the artistry was to navigate the least dangerous pathway for the dancers to take. My job during the shoot was to constantly sweep the floor. The soundtrack as well is a description of the building: we brought some wood sticks into the hollow underground spaces of the structure and recorded their echoes there. It’s “percussion,” but actually it’s a portrait of the building’s acoustic reflection.

What’s special about this project is that it forced me to adapt to different environments: the segment we just talked about is set in the below grade structure of what is now the building’s gym; we also filmed on the concrete foundation of its library, on a large lawn and on a ruggedly slanted paddock. There was no conventionally sized stage – so scale suddenly became the most important choreographic element. Scale, and the problem of space without physical boundaries. I’m used to having a wall or an audience to close the visual space behind the dancers; dealing with an open background was a challenge.

Echoes in the Grass, part of the Artists Warm-Up series at Grace Farms, New Canaan, CT.

Top photo by Adranna DeSvastich; bottom photo by Sasha Arutyunova; dancer: Cassidy Hall.

LH I feel like boundaries are so important in your work—the boundaries of one’s own body, the space one occupies, the edges of the stage, the space created by sound. As a choreographer, how do you navigate boundaries?

MM I think maybe boundaries are more important for the viewer. Something that guides your eyes, that gives you a sense of where to look, but also a physical sense of being cradled in a space that you share with the dancers.

At our home base at City Center Studios in Manhattan we have an interesting situation: the hall is a large rectangular box, but we set up the chairs in a diamond shape. The audience delineates a square stage that is rotated by 45 degrees in relation to the room. For them, the effect is ambiguous: am I facing straight, and the walls are diagonal? Or vice versa? It makes the choreography ambiguous as well: a dancer going from one corner to the next is perceived as going side to side, but we also sense that it’s a diagonal movement in relation to the walls. We have several nestled layers of boundaries.

I’d like to go back to talking about scale: we premiered a piece three years ago in a much smaller venue, the wood-paneled living room of a Gilded Age town house on Fifth Avenue, which at the time was unused. The audience sat in one row along the walls of the room. The remaining couple of feet in the center of the space were the stage (view here).

The dance ended up being about the feeling of being very close. The performance happened right in your face, with the dancers less than ten feet away from you, often just one or two feet. The music was by Ursula Mamlok, a composer with a fascinating sparse style that fit perfectly to the space. It was an extreme experience for the dancers too, especially since we tried to use a “normal” choreographic vocabulary – jumps, turns, things you’d do on a larger stage. They had to get comfortable dancing in the personal space of the audience.

We’ve toured this piece to several places, and it really depends on finding a suitable location: an intimate salon, ideally with a historic flavor. The actual shape of the room makes a difference; the original room’s dimension is embedded in the choreography. If we present it in a space that’s just a tiny bit wider or higher or with the door a little to the right – it feels completely different.

When we were talking about space being like an instrument – that’s what it is. You bring the dance to another space, it’s like playing the same music on a different instrument. It sounds the same, but not.

We had a different experience of scale recently during the pandemic. All the studios in New York City closed, and for several months we created a new ballet via Zoom from home. That is, in tiny Manhattan-size apartments. Each dancer was in her room on a 5x8 piece of Marley flooring, with the camera so close that it was rarely able to capture her full body. That’s how we choreographed the ballet. The movement phrases are much more complex than usual because the dancers had to change direction after each step or run into some furniture. It feels very dense. It’s a quartet, made one individual part at a time. Recently we had the chance to rehearse the work together in a large space, and it looks like nothing I’ve done before. Because it has this density and modular quality, even though it’s now grown to a normal scale. You still feel that it was originally very tight.

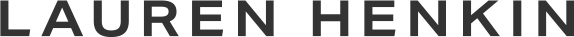

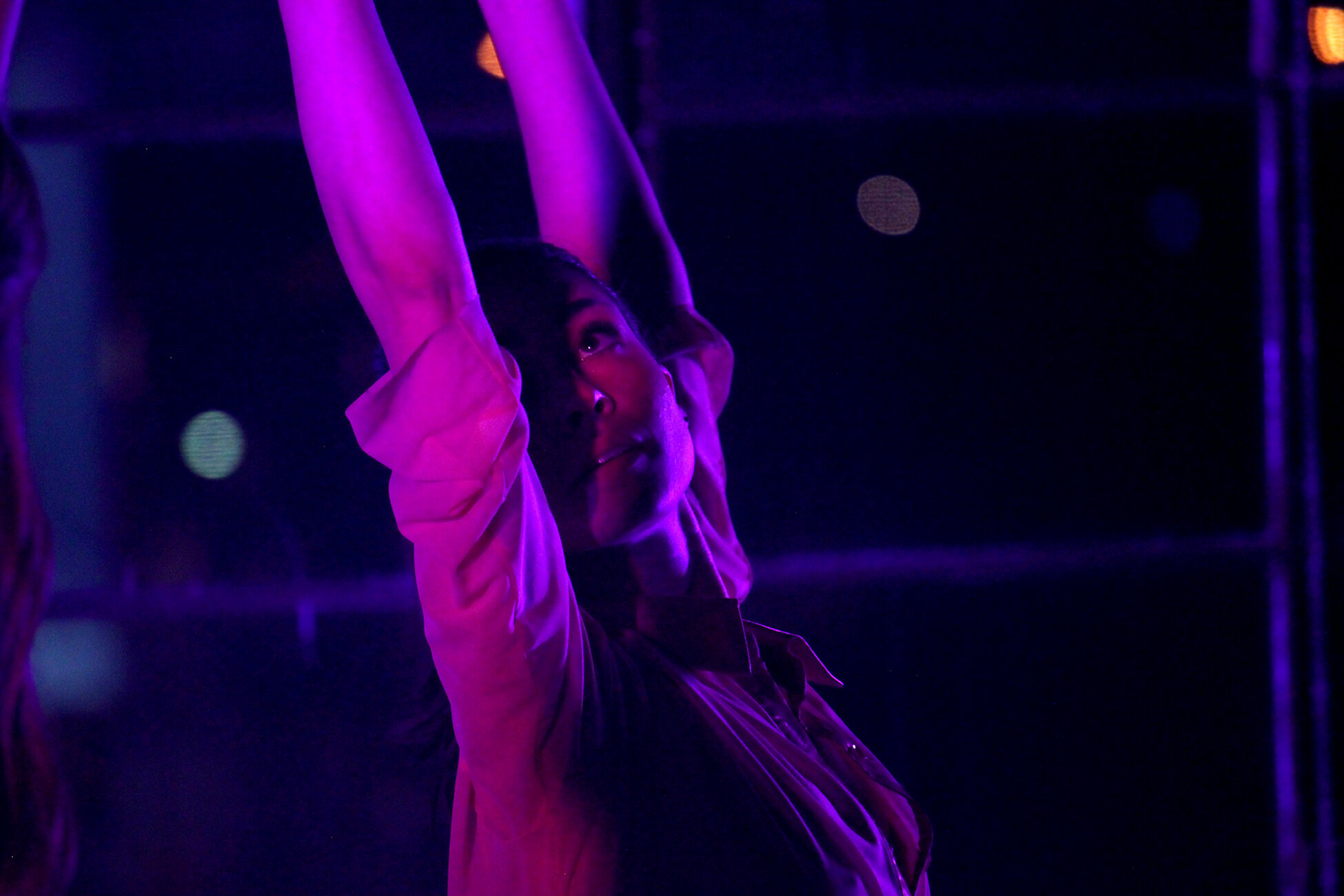

Stray Bird, New Chamber Ballet, 1014 Space for Ideas, New York City, NY, 2020.

Documentary by Anne Berrini (director) and Ronald König (camera) about the New York Premiere of "Stray Bird - A Danced Tribute To Ursula Mamlok" of the New Chamber Ballet. Choreography: Miro Magloire (Artistic Director New Chamber Ballet), Rebecca Walden, Mara Driscoll Music: Ursula Mamlok Costumes: Sarah Thea Dancers: Sarah Atkins, Elizabeth Brown, Kristy Butler, Traci Finch, Amber Neff Soprano: Cree Carrico Flute: Martha Cargo Clarinet: Carlos Cordeiro; The Momenta String Quartet: Emilie-Anne Gendron, Alex Shiozaki (violin), Stephanie Griffin (viola), Michael Haas (cello). © 2018 Berrini Films/ Dwight und Ursula Mamlok Stiftung.

LH There are times in many of your ballets where dancers seem to meld together and then break apart again. Do you choreograph for the dancers as individual elements, as parts of a whole, or somewhere in between?

MM It’s a bit of both. I would distinguish two situations: constellations and weight sharing. In a constellation the individuality of each dancer recedes in favor of an overall shape. You can tell that there are several bodies, but the predominant effect is of a single entity. Even if they’re not touching. Negative space becomes very important, and bodies are closer than is comfortable for the dancers: they’re in each other’s personal space, and can only move together as a unit - especially if they’re not moving in unison.

Once they come even closer and touch, they start sharing weight and the melding becomes more intense. The identity of each body starts to blur. You don’t know whose leg you’re looking at, or whose arm. It’s hard to distinguish. And since the dancers share weight, they can only move together. In fact, sometimes even for them this is confusing: where do “I” end, where do “you” begin? Maybe that’s what you referred to as boundaries.

When we get to weight-sharing moments, there is a very intense emotional connection for the audience: seeing another human lean, fall, rise and so on. It’s instant drama. It works with objects, like leaning elements in sculpture; but it’s even more intense if you watch living beings. Especially when the dynamic changes: now one person is on top, now the other. Even more disorienting, one dancer is often upside down, so directions lose their absolute meaning. You should hear us try to communicate in rehearsal!

When I choreograph these moments I don’t think of each individual dancer. In fact, I create them in the studio together with the dancers, giving them goals of how and where their weight should move. The final shapes often look so beautiful and sculptural that you’d think they were the goal all along, but in fact they’re just a byproduct. It’s really about an expressive exchange of weight in a duet.

That said, the basic premise of a dance is still a person dancing, alone or with (an)other person(s). As performers, the dancers are always individuals first. Seeing this individuality merge with another, and then return to being itself, that’s what makes it exciting to watch.

Top photo: Sanctum. Photo by Eduardo Patino, NYC, dancers: Rachele Perla, Madeleine Williams, Amber Neff, Traci Finch.

Bottom photo: The Night. Photo by Arnaud Falchier, dancers: Anabel Alpert and Amber Neff (kneeling), Rachele Perla and Megan Foley (on the floor).

LH Part of what I find so intriguing about New Chamber Ballet is the lack of individual lighting on the dancers. The dancers and the audience share a single plane of frequency. Why is it important to you that the dancers and audience coexist in this way?

MM The theatrical stages where we usually watch dance, even very cutting-edge dance, present us an elevated artist who says “watch me, I’m special, and I have something special to tell you.” It comes from a long Western European tradition, but this approach never resonated with me. When you’re an artist working at this level you know that you’re not special; you know that real art has to do with deepening the connection between human beings.

There are many different motivations why people dance: it has to do with the physical stimulation of music; with seducing another person; or with the extasy of synchronizing in a group. I wanted to preserve these in our performances. The first step was to let the dancers dance for and with each other, rather than for the audience. It changed the spacial structure of choreography: the formations faced inward, to the center of the stage. As a response we sat the audience around the dance area and brought them level. And into the same light. Now as an audience member you know that you’re in the same space as the dance. The same reality: the dancers are human like you, they breathe, and they sweat. You remain aware of that, while at the same time something superhumanly beautiful happens right in front of your eyes. That’s when art is at its most powerful: entirely grounded in reality and divine at the same time.

Our challenge at New Chamber Ballet has been to find venues outside of our hometown that will allow us to perform that way. Theaters and performing arts venues are built with the traditional separation in mind, and our setup is challenging for a presenter to accommodate. Theatrical architecture and the way most artists work create a pattern which is difficult to break out of.

Top photo: Sanctum. Photo by Arnaud Falchier, dancers: Amber Neff and Traci Finch.

Bottom photo: The Night. Photo by Arnaud Falchier, dancers: Megan Foley, Amber Neff, and Rachele Perla.

LH Since most live performances have been unable to resume with COVID, you have been creating movies, some with filmmakers and others where you have been shooting solely with your phone. What has this experience been like? Do you see the film as the final experience or do you see the filmmaking as one act and viewing a separate one? As you asked me once, I’ll ask you—why would someone want to see a dance film?

MM New Chamber Ballet is all about the live experience: the energy in the room when people do something and other people pay attention to it. Initially I had a hard time embracing the reality of dances made for film. The idea of sitting in front of a screen (or worse, a laptop or a phone) watching a recording of people dancing while hearing a recording of people making music seemed ridiculous to me. I couldn’t help but wonder, why would anyone want to see this?

So I tried to reconcile with it from a different angle: choreographing is learning how to see, and the camera allows me to see things I normally can’t. Experience moving bodies from very close, or from high above or below. It also allows me to manipulate time and continuity with extreme durations and improbable transitions. I find it extremely interesting: one is convinced to have seen something that never actually happened.

The camera gives me control over what is seen, but not over how it is seen: an interesting paradox. You could watch the film on your phone or on a large tv; in darkness or daylight; piecemeal or uninterrupted. The viewer is in charge of creating the best environment to enjoy the work. I trust that they will.

One of the films we just released, “Nocturne,” is a collaboration with the filmmakers kw creative, whose director and cinematographer, Emily Kikta and Peter Walker, each have an extensive dance background. They are both members of the New York City Ballet. As you can imagine, their camera work has a stunning physicality. A new experience for me: my choreography no longer defines the experience of space – their film capture and editing does. In a striking way, I might add: you feel like you’re dancing with the dancers.

Nocturne, New Chamber Ballet, Brooklyn, NY, 2020.

A Dance Film by kw creative. Directed by Emily Kikta. Choreography by Miro Magloire. Music: Johannes Brahms, Violin Sonata No. 1, op.78. Dancers: Anabel Alpert, Megan Foley, Amber Neff, Rachele Perla. Music performed by: Doori Na (violin) and Sean Kennard (piano). Camera operator: Peter Walker. Costumes: Sarah Thea. Costume assistant: Lauren Carmen. Filmed at: Please Space.

LH In 2004, you founded New Chamber Ballet. What exciting challenges do you look forward to in its next 16 years?

BC In my dream we would have a permanent home to rehearse and perform in, and to house our other activities like teaching or the visual arts residencies we’ve hosted. What would such a home ideally look like? That’s a really interesting question, one I think about a lot. It brings back the whole discussion we just had, about scale, boundaries, openness etc.

It also brings up the question of money and sustainability. Because one of the reasons the company has made it this far is our extreme financial austerity and nimbleness. Would a permanent home threaten that? Probably. When you’ve lived in New York City as long as I have you begin to think that access to space is a luxury and a privilege.

The other reason the company is going strong is that I try not to plan very far into the future. There is no master plan. Being aware of the needs of the moment and being genuinely committed to the growth of the people involved, those are the two guiding principles from which everything else emerges. The outer circumstances will continuously change! That’s an obvious thing to say this year, but it felt like that to me from the very beginning.

We’re part of a community, or rather of several of them, and it’s our responsibility to take care of our environment, our community, and its people, physically and emotionally to the best of our ability. That takes all kinds of forms. Problem-solving of the wounds affecting our society has been pushed to the forefront lately with an urgency that is at odds with the complexity of the injustices we try to address.

Our group’s small size puts us in a privileged position: everything can be addressed on a person-to-person level. Inside our group we can readily change patterns that are harmful or have lost their justification. Sometimes this happens instantly; sometimes it’s slow. We’re often out of synch with what the mainstream sees as the issue of the month, but paradoxically that gives us the freedom to come up with solutions that are more solid.

Maybe the biggest challenge we will face is how (not) to bring the past into the future. Ballet is obsessed with its own tradition. I respect and admire that. But for me “tradition” means to learn, to soak up energy from those who came before us, to understand their wisdom in problem-solving, and then to go and build something new with it. Trying to preserve and repeat successes of the past only highlights their flaws and inadequacies. I have no interest in doing that. Our art is still largely orally transmitted, and there’s an existential fear to let go. The stakes are very high: when there’s no written record you could lose it all at any moment. People die; and what’s gone can’t be recovered. It’s scary, and in a way that’s good. It’s what makes dance such a bold, courageous art form, and what makes me so proud to be part of it.

Gnomon, New Chamber Ballet, New York, NY, 2020.

A film by Miro Magloire Danced by: Megan Foley, Amber Neff, Anabel Alpert, and Rachele Perla Costumes by: Sarah Thea Choreography, camera, editing by: Miro Magloire New York City, 2020

Miro Magloire is the founder and artistic director of New Chamber Ballet. Magloire has created over 100 ballets for his company, all with distinguished choreography, theatricality and daring musical collaborations with singers, violinists, pianists and large ensembles.

Magloire's works have been commissioned by Joyce/SoHo, Roulette, the Moving Sounds and Sonic Music Festivals in NYC, the Sarasota Opera, Grace Farms Connecticut, the Center for Faith and Work NYC, and the American Academy in Rome, Italy; and performed at the Jacob's Pillow Inside/Out Stage, Ailey/Citigroup Theater, the Center for Performance Research, the Museum of Art and Design, and Bramante's Tempietto at San Pietro in Montorio in Rome, among other venues. He has collaborated with the Argento Chamber Ensemble, the Momenta String Quartet, Ekmeles, Variant 6, and in addition has created ballets for CelloPointe, Periapsis Music and Dance, the Columbia Ballet Collaborative, Central Pennsylvania Youth Ballet and the State Academy of Dance in Cologne, Germany.

All images and videos courtesy Miro Magloire and New Chamber Ballet. All rights reserved.